Survey says: More than a third of alumni polled said a cure for Alzheimer’s is one of the top breakthroughs we will see by 2050.

When asked which breakthrough they would most like to see by 2050, many alumni had the same survey response: The end

of Alzheimer’s.

It’s such a personal disease — one that robs family and friends of the very memories that make them, them.

It’s also widespread: One in 10 people age 65 or older has it, so it’s only natural that people are clamoring for a cure.

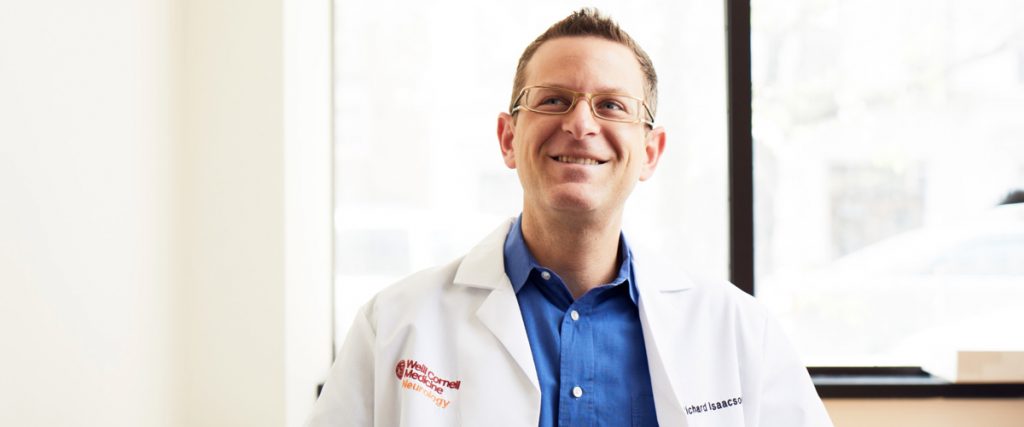

UMKC graduate Richard Isaacson (M.D. ’01) wants a cure, too. In fact, he has dedicated his entire career to it. Isaacson is the director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic at the New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City.

The key to a cure, he says, doesn’t just involve elderly patients. It will also require young people to tackle the disease years — and sometimes decades — before they show symptoms.

“The future is now”

When patients come to Isaacson’s clinic with symptoms of Alzheimer’s, they’ve likely had the disease for 20 to 30 years. This is part of the puzzle of curing Alzheimer’s: Once a patient begins to experience memory loss, the disease has been building for decades.

How to overcome that? Catch the disease in its infancy, when a patient is 50, 40 or even 30 years old.

“When it comes to Alzheimer’s, I really believe that the future is now,” Isaacson says. “To cure Alzheimer’s disease, you have to treat it before symptoms start.”

Isaacson’s oldest patient is 91 and his youngest is 25. So when is the best time to talk to your doctor? The earlier the better, he says, especially if you have a family member with Alzheimer’s.

“What we can do is recognize the people at the highest risk, and make very specific, targeted changes in their life to reduce their risk,” Isaacson says. “That’s really the way things are going.”

Another reason to get tested early: Research suggests one in three cases of Alzheimer’s may be preventable. And new technology is making it easier than ever to diagnose.

Technology and Alzheimer’s

Most patients are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s through a series of questions and tests in their doctor’s office. Isaacson hopes that eventually, doctors will be able to raise the alarm about their patients’ cognitive function long before that person notices it themselves.

“I hope that one day we can give somebody an iPhone app and say, oh, this person is texting more slowly than they used to, or they’re taking longer to answer the phone, or they’re making more errors,” Isaacson says.

Some of this tech-enhanced testing is already in use. Alzheimer’s Universe, for instance, is a free website focusing on prevention. Visitors can use a webcam to track eye movements and determine the health of their visual memory. Another application allows users to play a matching game, but with a twist.

“You think it’s like the memory game for kids, but it’s way more sophisticated than that,” Isaacson says. “We’re tracking how quickly the person is tapping the button, if it’s accurate, where they’re tapping the button — we’re doing all these fancy things on the back end.”

The earlier people can be identified as being at risk for Alzheimer’s, the earlier experts like Isaacson can create a prevention plan tailored to their exact needs.

Finding “the cure”

The cure for Alzheimer’s won’t be a singular solution, Isaacson says. Instead, it will be a combination of drugs, vitamins, supplements and lifestyle changes.

In other words, says Isaacson, “There’s never going to be a magic pill or potion.”

Instead, doctors will create a prevention strategy that targets what Isaacson calls the ABCs of Alzheimer’s: Anthropometrics, blood biomarkers and cognition. In layman’s terms, that means looking at factors like body fat, genetics and scores on memory tests to determine the best treatment for each individual.

Isaacson’s personalized plans go much further than advice like “eat healthier” or “do more puzzles.” He and his team hone in on what specific types of foods should be added or subtracted from a diet; whether cardio or strength exercises will be more effective; which brain teasers will target the specific cognitive function that is faltering, etc.

The key is to make the treatments as individual as the patients themselves. And those strategies are getting more advanced every day.

“The textbook on Alzheimer’s prevention hasn’t fully been written yet. There’s maybe the first chapter or two, and then hopefully we can help write the rest,” Isaacson says.

It’s not a cure, but it’s a start.